PROTOTYPE 1: Land and Sea

- ajmakesthings

- Nov 6, 2019

- 16 min read

Updated: Feb 3, 2020

I am dubbing our first game idea "Land and Sea" as that seems to be what defines it as the idea evolves. This idea began with my desire to make a game about stories within stories, which I thought would be visually captured by the stark contrast between a world above water and a world below.

The first piece of development on this project came in the form of an incredibly crude paper prototype that was crafted in the style of an old-school View Master, in which looking through a lens allowed you to flip between worlds at whim.

The idea here was that through the first tube, which represented the under water world by the border of sea-bed and fish, you could rotate through three other worlds and look at them through that lens. Despite being incredibly rudimentary, it was quite an effective way to communicate the idea.

I liked the idea as well that the worlds were all separate and didn't need to be connected at all, and that with this idea we could explore a variety of contrasting environments, which was of interest to all of the team members.

From here I took my research and experimentation into storytelling and applied it to the idea.

Choosing the third of Kurt Vonnegut's six basic plots, Man in Hole, I revisited the research I'd done on journeys to look at cyclical stories and ending the tale where it began to showcase the character development undertaken through the story. The dark purple represents the playable game, which consists of a character travelling home and telling three stories (indicated by the three circles numbered 1-3). Those three stories relate to three events that happened offscreen, and are small allegories for the experiences the character had. The story culminates with the character returning home, and the player realising that the stories told by the character were their own the whole time.

A team discussion alongside this development started to shed light on the kind of setting we were interested in using, and we liked the idea of a seaside town/island that was jaunty and stacked up. Kerris drafted some concept art for this idea, which I then took and applied to this story structure I had in mind.

I drafted a narrative for this, which I named Pocket Stories The first draft of the narrative followed the main character as they returned from a journey to their home - a series of inhabited islands that they must traverse. They encounter obstacles as they go, and exchanges her stories for passage to the other islands. The story is one solid narrative about a fish that leaves their school to find treasure, and the three key lessons they learn whilst they're out there: how to be independent, how to accept help, and how to help others.

Testing and changing

I mocked up this image to visually represent the journey, and tested the narrative by telling it to my family, who had a lot of holes to pick in it. Their major criticism was with how I was justifying the fact that the narrative is just one story broken into three parts, but is told to three separate groups of people - logic would argue that all the characters that were audiences of the story except for the player would be confused by the excerpt of the story they were told, as they would not receive a full beginning, middle and end.

I struggled with this for a day or so, trying to create three individual stories instead of just one big one, but had little luck. That week we were visited by guest lecturer Emma Joy Reay, who Sid and I asked for help solving this problem, as between the two of us we couldn't figure out a way to. She had a lot of suggestions and input that are documented in my narrative design blog, but simply retelling the story to her coupled with the lecture she gave on child-characters in gaming allowed Sid and I to bounce ideas off each other until we solved our problem by creating a consistent character that the main character bonds with on her journey and tells the story to in its entirety.

The reason her lecture helped with this was that she examined how younger characters in games are presented, often stripped of flaws and the pinnacle of innocence. This inspired me to create a character that could challenge these stereotypes, and this character existed in my working draft. By taking that character and giving them more agency, I was able to create a two-way dynamic between the main character and this child character that did a lot to bolster the integrity of the narrative.

Having drafted up the second draft outline for this story on Twine, I took the story to my team for more feedback. Kerris noted that she didn't really connect to the main story, and was more interested in the story about the fish than the one on land. This was difficult for me because in the time I'd been working on this idea I'd become quite attached to the character even though they didn't have a name or a physical form beyond some concept art I'd created to get things moving in my brain.

Despite this, I knew the importance of this phase for throwing out ideas that didn't work, and Kerris expressed that she didn't think there was a lot of playability involved in the story that takes place on land, and that despite wanting the game to be narrative-driven, that didn't necessarily mean she was happy with the narrative being the sole driving force of the game. Whilst I personally disagree, and think plenty of games showcase the power of narrative by essentially acting as a playable piece of cinema (e.g. Detroit: Become Human, Death Stranding, etc.) I do appreciate that this is a collaborative project and want to make the game fun to play as well as generally a good narrative experience.

Idea pivot

One of Kerris' key points in her criticism of my first idea was that the connection between land and sea didn't seem strong enough, and after examining the idea more, I can agree. So the whole team got together to chew over the idea, picking out what we liked and didn't like about it. We all agreed that we wanted to keep the contrast between land and sea, and that we wanted this game to be single player and to be character focused. We also wanted to keep the first theme we agreed on in the ideation phase: "We are better when we work together", but decided to change it across all three ideas to be "community".

In order to connect the sea and the land together, we thought it might be interesting to have them coexist in the same universe, rather than exist separately in two different worlds (such as the creature on land telling a story about life underwater). We went back to Kerris' initial drawing of the stacked island, focusing on the underside, which sparked an idea about collaboration between two characters living on two sides of the island.

From this an idea sparked about the island having turned upside-down, displacing all the residents on either side as it did so, and leaving the animals above water on the side of the island that used to be submerged, and the underwater creatures in a new environment underwater that used to be above. We liked the idea that the characters would have to figure out why the island turned upside down, reinforcing the theme of community by showing the interaction between two societies that previously didn't know the other existed. Every time the player switches character (to be confirmed as its own mechanic or a scripted event) the island would flip and you would be able to play from the upright perspective of the other character.

We crudely visualised this idea, with a community on either side of the island.

The core mechanic would be that these two characters would have to communicate to each other on either side of the island in order to uncover why it flipped over. We decided a poignant cause for this would be because one side of the island got greedy and over-built, unbalancing the island and sending it toppling over. We speculated that perhaps the characters could use the player as a relay, and the player could be acknowledged within the narrative. This could potentially be a meta way of explaining how the characters came know the other one existed.

From here we ideated that the core gameplay would revolve around the characters having to get objects to each other to help them solve puzzles on either side. Each time a character's path would be restricted, they would need something from the other to continue. Through this, they could learn each other's stories. I mocked this up very loosely using Twine with placeholder characters Olivia the Otter and Connor the Crab to show how the back and forth could work.

We tested our idea by telling others of our plans, making sure we discussed with a variety of people, some who had backgrounds in gaming and some who didn't. The best initial feedback we received was from my brother, an avid gamer and coder who questioned the necessity for the player to be involved in the narrative in any way, especially if Olivia and Connor would spend their time uncovering each other's stories. We had implemented this idea as a way to lampshade the characters not having proper motivations for collecting items and sending them to the other side of the island, but my brother's criticism made sense and showed that by trying to avoid one issue we were creating others for ourselves.

From there, Sid and I developed the idea until decided that these issues could be solved by the narrative. Instead of the characters acknowledging the presence of the player and their omniscience in knowing what to send to the other side of the island, we could just make the characters communicate, which would add to the puzzle element of the game. For example, the communication could begin with Connor the Crab needing to find a bottle to write a note that he sends to the water's surface requesting an item. Olivia the Otter then finds the message in the bottle with the request inside, setting the story in motion. The challenge in gameplay then comes from discovering certain ways to communicate between characters, and the relationship between them becomes a personal one. This would also help to drive home the theme of the community - letting the player watch two characters they control interact with each other and learn about each other's lives.

During this ideation process we were visited by Mink Ette, an escape room designer with experience in puzzle design. Her lecture was extremely helpful in generating puzzle ideas for us. She discussed many things about puzzles, but one of the most interesting things I took from it was her discussion about the relation between escape rooms and theatre.

She talked about perceiving puzzles as existing through space and time, and blocking physical puzzles, i.e. arranging puzzle elements in a certain way in a physical space. I have a theatre background, and had never considered using this as a way to design games, specifically puzzles. It helped me connect narrative to puzzles better in my head, knowing that actually story has a really big part to play in terms of how the puzzles can be solved.

With this newfound inspiration I started to think about games that could inspire me in terms of merging narrative design and puzzles. The first game that came to mind was Broken Age, a single player point-and-click about two characters whose stories intersect.

I bought and played this game for iOS, and was immediately interested in the fact that as a player I had the freedom to change between characters at will, chopping and changing between stories. It was also exciting to spend hours with two characters existing in supposedly separate worlds, then have them join to gather in a narrative climax at the end of the first chapter.

Having two main characters in Broken Age confirmed my belief in the importance of dual protagonists. I grew very attached to these characters, invested in their worlds, wants and needs. When they eventually met in the story, if only for a moment, I was more emotionally invested in that moment than I think I would have been had I only been controlling one of the characters.

It also opened my mind to the possibility of making the game a point-andclick, as Broken Age does quite a good job at not letting the mechanics get boring. However, I think there is sometimes an issue with point-and-click games when it comes to pacing, which is integral when it comes to narrative delivery.

As a team we were discussing lots of ways to create puzzles, and characters whose traits could contribute to the solution. For example, Kerris suggested having an electric eel whose electricity could be used to light up a wire used for communication. After a conversation with our course leader Adam, however, we realised that we were getting too caught up in specific mechanics when we hadn't nailed down our core narrative yet. I had been resisting leaning too far into the narrative for fear of inhibiting other team member's abilities to be involved in the design process. However Adam suggested that with the narrative nailed down we would be able to shape the design of the gam around it.

We were also struggling knowing what kind of gameplay to use for this game. Because our theme is "community" and we have two main characters, people were continually suggesting to make the game co-operative. I really didn't want to do this, and feel I have plenty of evidence as to how games with multiple playable characters work well if not better in single player. Afterparty is a single-player game in which the player switches between the two protagonists, best friends Milo and Lola. As previously mentioned, Broken Age shows how two main playable characters can increase the emotional impact of the narrative. Valiant Hearts constantly switches between a cast of four characters whose stories intersect and are related. Thomas Was Alone has ten playable protagonists who work together to complete the game, each endowed with individual personalities that cause the player to be deeply attached to the cast.

That said, Kerris was open to exploring other ideas, so Sid and I ideated with her on what kind of game we would be making. We came up with four options:

1. Single player game: story directs the player.

2. Single player game: player can flip between characters.

3. 2 player couch co-op: More efficient, two controls. Players can collaborate and explore at free will.

4. 2 player Online multiplayer: Experience one side of the story and then go back to experience the other

We haven't decided which of these to choose, and intend to test the different game types to see which is more effective.

Narrative

We began by defining three core experiences that we wanted to be taken away from the game. After some thought, we decided on:

Irreversible Change

Exploration of Environment

Learning from Others

Using some of the techniques mentioned in the narrative design blog, I began by thinking about the shape of the story that I would like to tell. While I was initially attracted to the Man In Hole story, I found that once I plotted the movements of the narrative as discussed by the team so far that the story shaped itself to adhere to the Cinderella structure instead.

Taking Adam's advice, I broke the narrative down into three acts which I planned to organise systematically as I fleshed them out.

I turned this graph into a document, which I split up into acts and then categorised by characters, actions, and the core experiences we came up with. I've never designed a narrative so systematically before, and found it quite a challenge. I like there to be an organic element to the process, however I benefitted from plotting the general movements of the plot and so knew what goals I was trying to reach with my story at any given moment.

Whilst I had developed our two main characters, I initially left the character section blank in terms of NPCs, not wanting to include a character that wasn't necessary to the plot. As I went along, I faced obstacles, for example, in the first act when Arty breaks his glasses and needs to ask for the key to the optician from Fi, I realised that if he couldn't see well enough to move, he probably couldn't see well enough to write. So I created the character of Sachi the squid, who could write with his ink on his behalf. The appearance of the character required me to flesh them out in terms of personality, giving him a name appropriate for the place their species normally lives, and associated personality traits as per my research into fables. This is how I tackled this for each character:

1. Find a species that fit the needs of the task at hand.

2. Consider the anthropomorphised "personality" of the species, and translate that into individual wants and needs for the character.

3. Research the main habitat for the species.

4. Find a culturally relevant name based on this information. Try to relate this to the species through either alliteration or subject, i.e. Sachi Inkeda - Sachi is a Japanese male name, the S is for squid, Inkeda is a corruption of the Japanese surname Ineda to relate to squids producing ink.

This process continued over the three acts of the story until I had managed to adequately flesh out the narrative. I then went through each act and made sure it had elements that satisfied the three core experiences, meaning there would be consistent themes tying the narrative together.

Visual Style

We wanted the visuals for this game to be 3D, hoping that this would give depth and dimension to a world that 2D visuals wouldn't do justice. We imagined building a single environment that the camera revolves around, similar to that of The Gardens Between, which is our key visual inspiration for this project.

Kerris and I drafted some concept art for this imagined environment, depicting how this tight-knit community might exist and also the styles of buildings they might have created.

We also looked at Tunic, an unreleased game about a little fox warrior which is very inspiring in terms of animations and minimalist but polished visuals.

What we particularly like about this is that when the fox enters a room, it becomes a single box against a black background. This is incredibly effective in isolating the area and focusing the player on a given task. It would also add depth to our island, by making the houses something to interact with. Instead of having presentational houses that are just there to look at, everything is purposeful.

Character Design

Something I've realised with this idea is how important the characters will be to the story. If the story revolves around learning to communicate and appreciate others whilst still maintaining your individuality (and that individuality being seen as a gift), then the design of the characters will be crucial to people's response to it.

I have already mentioned Olivia the Otter and Connor the Crab previously, and I mocked up some designs for them to get an idea of style and personality.

Olivia was easy to ideate, there have been lots of other otter characters drawn before. They are a commonly anthropomorphised in media and loved by many. I wanted her to have attitude, to push against the female character stereotype in being anti-social and a bit grumpy, but intelligent and resourceful. With this in mind it became easier to visualise and sketch her. Feedback from social media told me I'd succeeded here, they loved the attitude I'd injected into her design.

In drawing Connor, however, I realised it was difficult to make him look like he appeared alongside the other characters. Sid had previously mentioned making an axolotl one of the creatures we could use as a character, and I revisited that idea and did some research.

As it would turn out, the axolotl is an endangered species, predominantly lake-dwelling from Mexico that is being displaced by pollution and urban sprawl.

The issue with the axolotl was that it didn't live in the ocean. Sid suggested making it a refugee, who had travelled far to find a new home, which I felt was really on-brand for this idea, considering that the cause of the island turning over is overbuilding by the land-dwellers. I felt that the character should still be helpful and cheerful like Connor was, and looking at pictures of axolotls they really do look happy, if not a little timid. Because of this I designed him with a reserved, meek posture, and gave him glasses to accentuate his personality by making him appear stereotypically nerdy. We named him Arturo, a popular Mexican boy's name which we've shortened to Arty.

My classmate Bill noted after seeing these designs that the otter can swim, potentially defeating the point of convoluted communication considering that the character could just swim down to talk to Arty. The axolotl can be on land too, but for less time.

I liked the similar shapes between the otter and the axolotl, however, enjoying the land/sea mirror image they created.

I started looking up endangered animals with a similar body shape that looked like otters, and came across the Black-footed Ferret, who lives in the grasslands of North America and has been similarly endangered by humans. Keeping the same personality, I mocked up another character design for our new character, Fiona the Black-footed Ferret. Placing them side-by-side helped me visualise them, and has definitely inspired the design of the narrative.

Narrative

Prototyping

Prototype One:

I made a prototype that showcased the mutual communication mechanic in its most basic form. Having play-tested this with several people there are some issues here to amend about affordance and comprehension, but it's a good working prototype to demonstrate a key idea.

Testing: The first time I tested this prototype I gave far too much information as to its purpose which meant that the tester wasn't experiencing it in its most base form. I learned from this when testing on others, giving them no information whatsoever and seeing how they interacted with it. Most people understood the idea of passing things back and forth between the characters, but some of the interactions required to transition between frames weren't obvious. Unfortunately, Marvel has a built in system which highlights the part of the screen that the interaction has been attached to as soon as someone mis-clicks, meaning it was difficult to determine the best way to fix this to make it more obvious.

Reiterating: I made a second version of this prototype with some sanity checking in terms of where things were positioned and why, whilst also making more steps and transitions, like adding a key pick-up and then walking to the door before opening it. As a general rule, testers understood that the prototype showed two characters with things they need working together to achieve or obtain them. But there was still difficulty that came with having a two-sided world only shown from one angle. In my third version, I kept all the transitions the same but changed the orientation of the image depending on which side of the island the player was on. This helped make the process of controlling both characters individually much more clear.

Prototype Two:

Our second prototype was a physical one. I glued cardboard toilet rolls together into the same shape proposed for the island, with overlapping or intersecting passages through the rolls. The main purpose of this is to showcase both the need to send items to the other side of the island and the dual-gravity system. The latter is shown by flipping the cardboard model over and being able to use the gravity to send the item back to the other side of the island.

Testing: In testing this prototype I gave people the island and a small object and asked them to interact with it, giving them as little information as possible. 100% of the time, they posted the object through the island so it fell out the other side. I'm pleased with this response, and whilst the dual-gravity idea didn't shine through as strongly as I'd intended, I'm really glad that people saw the purpose of the toilet rolls as different passages to send an object through.

Prototype Three:

Sid designed a prototype that flipped the camera between two characters on either side of the island. He also included a post-processing element that meant the underside of the island was blue-tinted as it would be underwater, and the topside of the island was not. His development of this prototype can be found here.

Prototype Four:

Kerris prototyped animations for some of the mechanics we could use in terms of how the characters would communicate with each other from either side of the island. Her development of this prototype can be found here.

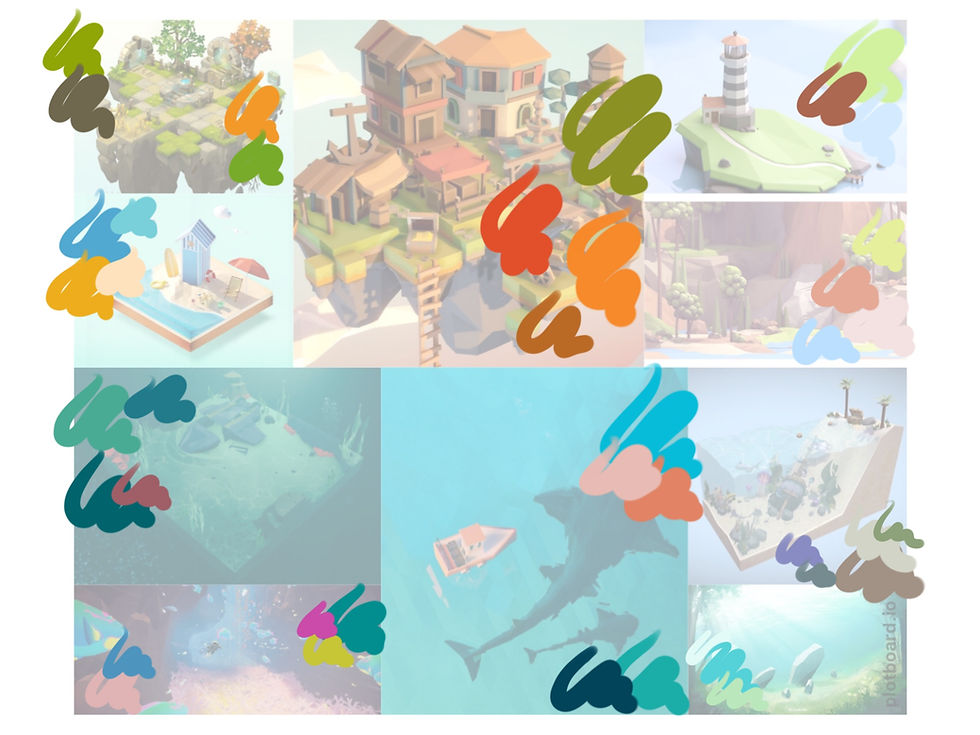

Moodboards

I created a variety of mood boards to help visualise the different styles of art we could use, as well as characters, colour palettes and general mood.

This moodboard is intended to help convey the general mood of the project.

This board is designed to show the divide between the top and bottom sides of the island.

This is a collection of colour palettes that we could use when creating assets.

If we were to take the project forward in 3D, this moodboard suggests what the buildings might look like.

I also visualised how the world might look if we were to take the project forward in 2D.

A moodboard for visualising Arty the Axolotl.

A moodboard visualising Fiona the Black-footed Ferret.

Comments